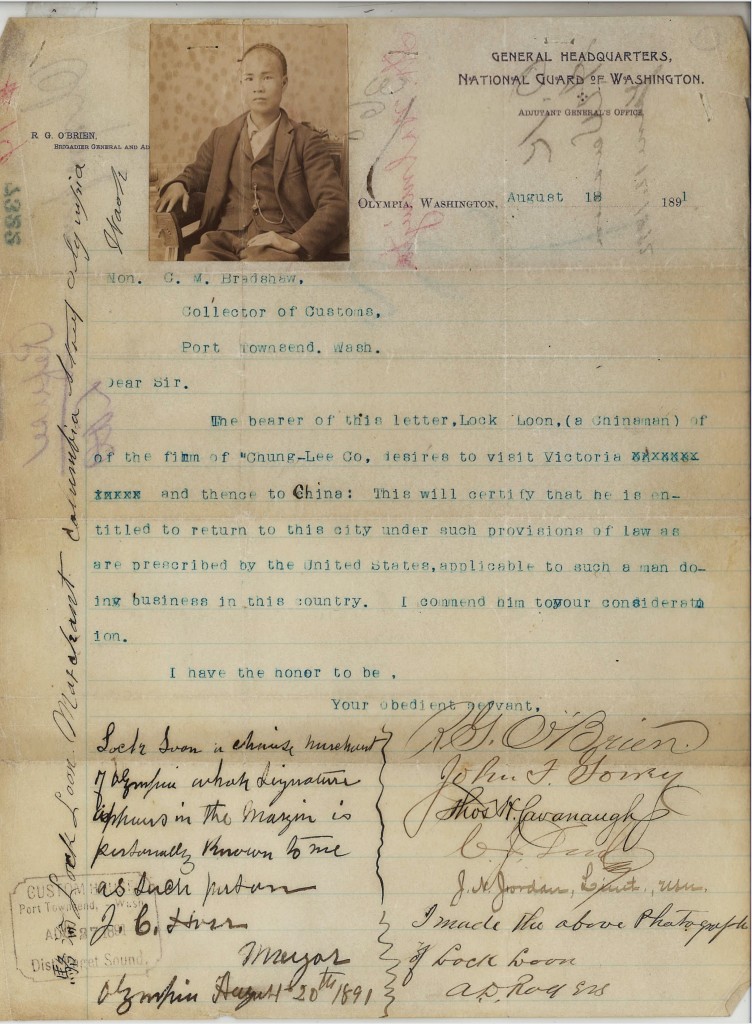

On 18 August 1891, Rossell G. O’Brien, Brigardier General of the Washington National Guard, signed an affidavit stating that Lock Loon (Lock Ling) of the Chung-Lee Co., Olympia, Washington, wished to visit Victoria, B.C. before making a trip to China. The document certified that Lock Ling was entitled to return to Olympia, Washington. James C. Horr, Mayor of Olympia, added a note saying that he knew Lock Loon personally. Lock Loon signed his affidavit in Chinese characters. An undated form from the Treasury Department said Lock Ling was admitted.

[Lock Ling’s file contains many pages and forms and covers the years 1891 to 1944. Sometimes the information is repetitive; frequently it is confusing and raises other questions. The file and therefore this summary is not meant to be a biography. Immigration officials used a series of interviews, affidavits, witnesses, and other documents to evaluate if they should admit someone to the United States. There were numerous restrictions and they wanted to make sure they were not admitting laborers, or anyone deemed unacceptable under the Chinese Exclusion Act. It was a complicated system.]

[The names Lock Ling and Lock Loon are interchangeable in these documents. This summary of the files will use the name the way it was spelled in the actual document.]

Rev. Clark Davis and C. P. Stone of Seattle were witnesses for Lock Ling’s trip to China in July 1897 and when he returned in September 1898. Lock Ling moved from Olympia and was then working at Mark Ten Suie Company in Seattle.

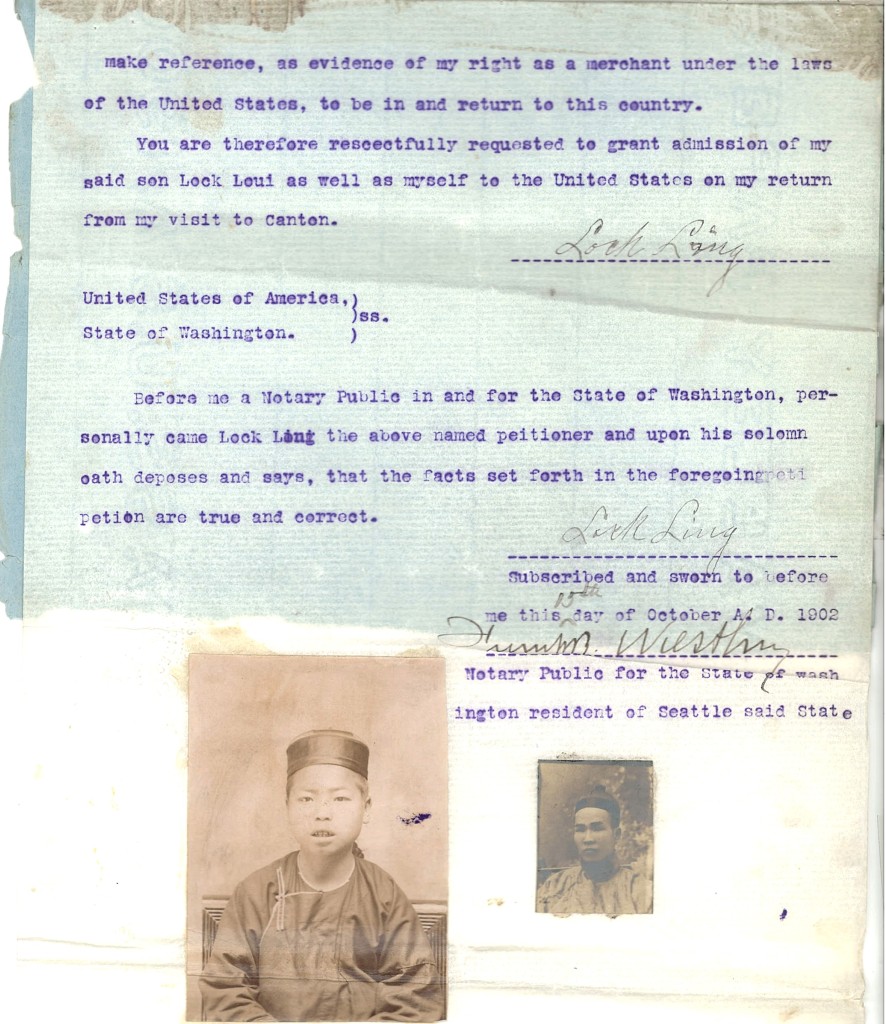

In October 1902 Lock Ling wished to make another trip to China. He swore in an affidavit that he was thirty-six years old and had lived in the United States for twenty-one years. He was currently a merchant for Coaster Tea Company. They sold teas, coffees, and spices in Seattle. He wanted to visit his family in China and bring back is son, Locke Loui, who was fifteen and a student. He attached his photo and a photo of his son to his affidavit. Harold N. Smith and Clark Davis were his witnesses. His application was approved.

Section 2, S.21039 of the Chinese Exclusion Act was updated and made stricter in 1893. It was no longer enough for a witness to testify that an applicant had not engaged in manual labor for at least one year before his departure from the United States, the testimony had to show specifically the kind of work the applicant did during the entire year. This did not present a problem for Lock Ling.

On his return trip in July 1904, he was admitted at Port Townsend, Washington. The record does not show if his son, Locke Loui, was with him.

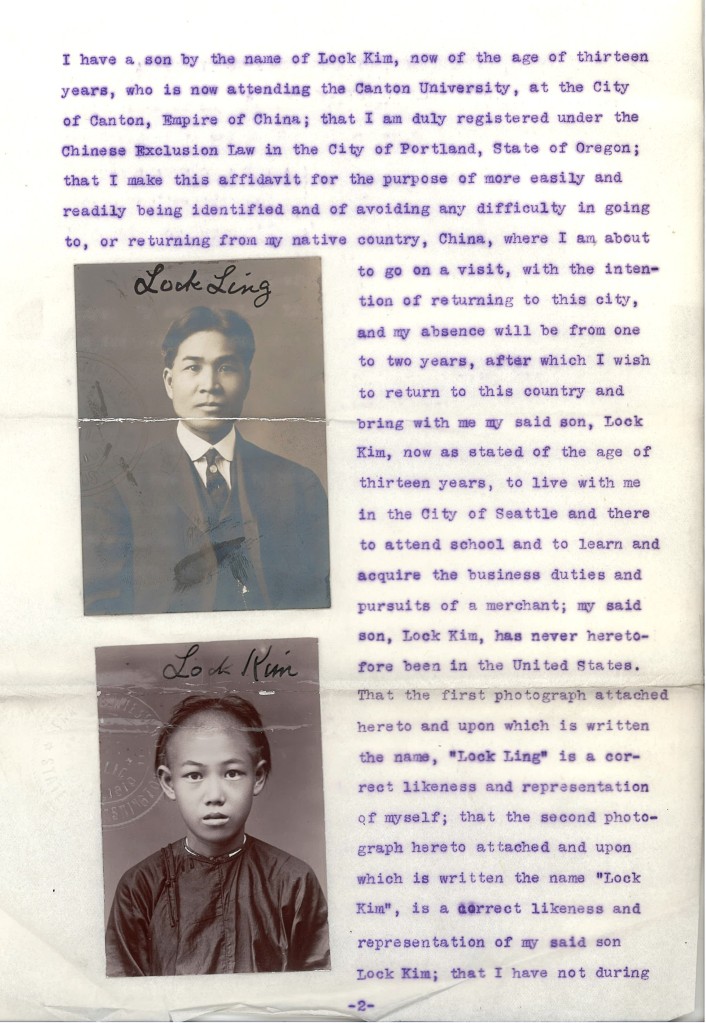

In March 1910 Lock Ling (Lock Loon) declared in an affidavit that he was forty-four years old; that he had been in the United States for twenty-eight years; had been a resident of Seattle for sixteen years; that he was a merchant for the last three years with Wing Long & Company; had recently sold his interest in the business; and became of member of Hong Chong Company. He wanted to visit his second wife, Lee See at Sing Ning City, Canton. His first wife had died, and he wanted to bring his son, Lock Kim, age thirteen and a student at Canton University, back to Seattle with him. He attached photos of himself and his son to his affidavit.

P. K. Smith and George O. Sanborn, both citizens of Seattle, swore in affidavits that they knew Lock Ling more than three years. They swore he was a merchant and performed no manual labor except what was necessary to conduct business as a merchant.

When Lock Ling was interviewed, he testified he was married and had three sons, Lock Loy, Lock Yen/Ying, and Lock Kim, and a daughter. His son Lock Ying was admitted in 1908 and living in Seattle; and Lock Loy was declared insane in a hospital in Steilacoom and went back to China. Lock Ling had been back to China four times, once before the Exclusion Act was passed.

The Immigration Inspector made a note on Lock Ling’s interview saying Lock Ling was well known as a salesman for Wing Long Company. His new firm, Hong Chong Company, had forty partners. He would be their treasurer; they sold drugs and general merchandise. The company was not incorporated under Washington State law but according to Chinese custom. They had a four-year lease from Mrs. W. D. Hofius for the four-story brick building, still being built for $950 per month.

Lock Ling’s application was approved, and he left for China in March 1910. He returned in October 1912 and was interrogated when he arrived. He gave his marriage name as Yin Ling and his childhood name as Lock Lung. He was returning from his fifth trip to China with his third wife, Wong Shee, his son Lock Kim and his daughter, Lock Mee. He had three sons and a daughter with his first wife who died about 1902. His sons Lock Loy, age 24, had been in the U.S. but went back to China about 1909 and Lock Yen, age 19, was in Seattle. His son and daughter, Lock Gim and Lock Mee, were in the detention house waiting for approval to enter the U.S. Lock Ling’s second wife, Lee Shee had a son, Lock Goey, who was still living in China. When Lee Shee died, her son Lock Loy carried the incense jar to the cemetery. Lock Ling then married Wong Shee according to the Chinese custom. For the ceremony, she did not wear a veil but the tassels from her coronet hung down over her face. She was brought to his house in a regular red, blue, and green sedan chair.

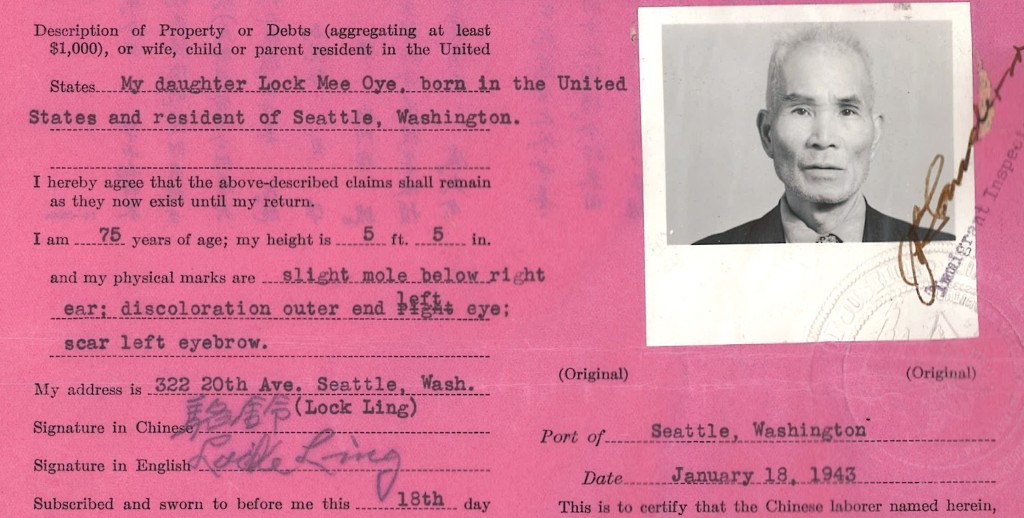

When asked, Lock Ling described his property in China: a house and rice land worth $3,000 Chinese money, and a building in Hongkong worth about $15,000 Hongkong money. He boasted that he went to China five times and a child was born as a result of each trip. In January 1943, Lock Ling (Lock Loon), age seventy-five, applied for a Laborer’s Return Certificate to visit Vancouver, B.C. He qualified because he owed his daughter, Lock Mee Oye, born and residing in Seattle, Washington, more than $1,000. He presented Immigration authorities his Certificate of Residence #55720 which was issued in Portland, Oregon in 1894. It showed that he was born 11 May 1868 in China and entered the United States with his father about 1882 at San Francisco at the age of fifteen. He lost his original Certificate of Residence #44577 so he presented his replacement certificate. His application was approved, and his current photo was attached to the document. Lock Ling and his wife went to Vancouver and returned to Seattle four days later.

Lock’s Reference Sheet shows three files were brought forward and gives file numbers for his wife, four daughters, and two sons.

[According to Hao-Jan Chang, CEA NARA volunteer and Locke family expert, Yen Ling Lock and former Governor Gary Locke are distantly related. They have common ancestors, starting from the first generation to the third generation. Yen Ling Lock is of the19th generation. Gary Locke is of the 25th generation.]