A big thank you to Kevin Lee of Australia for today’s blog post. Kevin summarized about 150 pages from three family Chinese Exclusion Act case files to give us a peek into his family history.

[The National Archives is still closed because of COVID-19 but the staff is working on a limited basis. They are taking requests for copies of files so get on their waiting list. If you would like a file, call or send your request to Archival Research, 206-336-5115, seattle.archives@nara.gov – THN]

Chin Hai Soon AKA Chan Mei Chen 陳美珍, home domestic (September 1904 – 29 March 1982)

She was the daughter, the granddaughter, the wife, the sister, the aunt, the great aunt, the grandmother, the great grandmother of Chinese Americans.

One of the significant consequences of Congress passing the 1875 Page Act and multiple Chinese Exclusion Act (CEA) bills in 1882, 1892, 1902 and 1904 was that Chinese women were kept out of the United States. Female immigration to the U.S. was made extremely difficult, and it resulted in families being kept apart for years or decades. Without women, there would not be family, progeny, children, lineage – the Chinese population in the U.S. would just die off, which was the intention of the laws.

I learned more about my grandmother’s life 40 years after she passed away, than when she was alive, by visiting the National Archives at Seattle in November 2019, prior to the Coronavirus shutdown. The National Archives of Australia (NAA) operates similarly to the National Archives and Records Administration in the U.S., and Australia also had the ignominy of slavery (where the Indigenous / Aboriginal population suffered) and the White Australia Act (which excluded non-Europeans from immigrating; a policy just as discriminatory as the CEA).

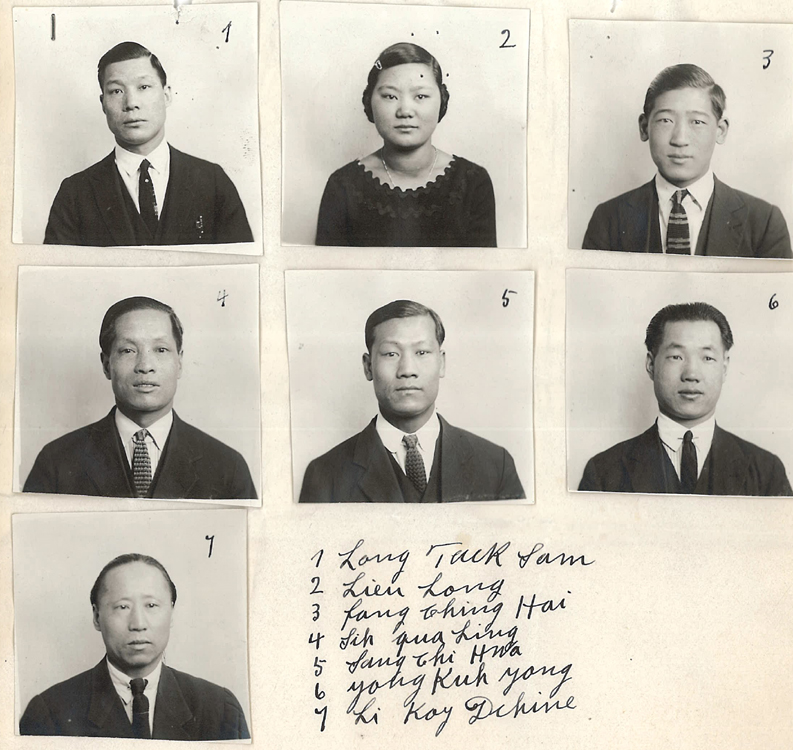

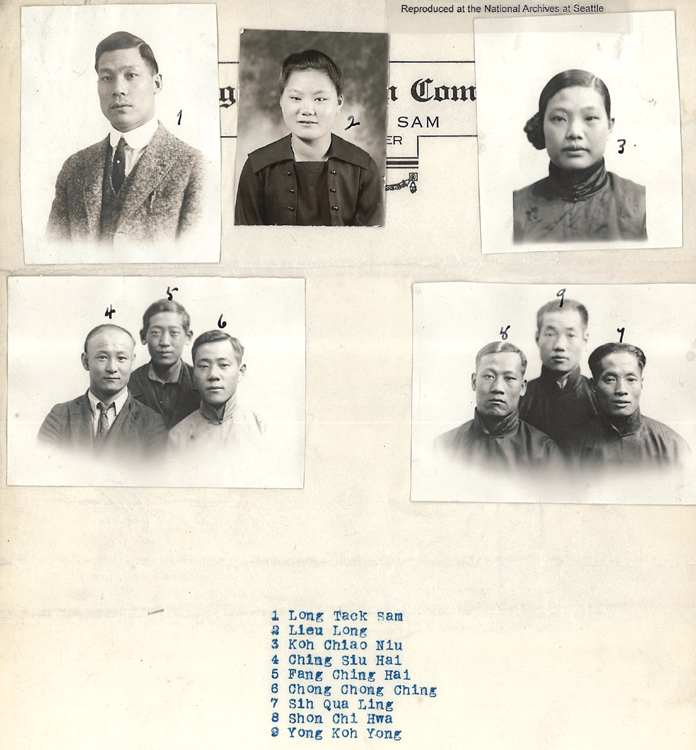

Chin Cheo 陳超 and his family details, including daughter Chin Hai Soon, on an affidavit dated 26 December 1925, Chinese Exclusion Act case files, National Archives-Seattle, #7031/325.

From these 3 important CEA files in the National Archives facility at Sand Point Way, Seattle:

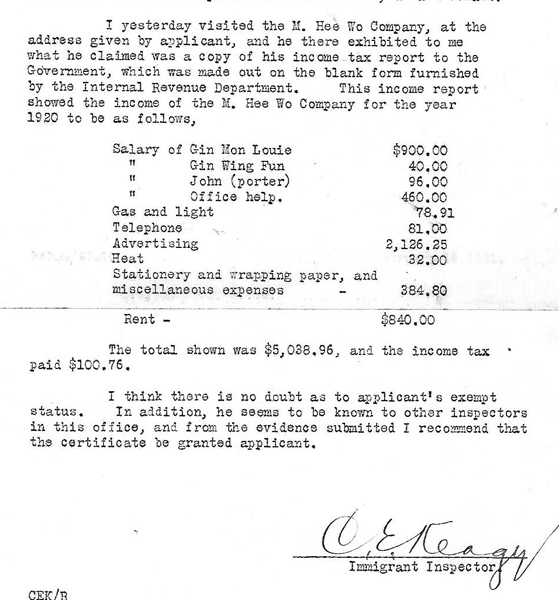

- Great grandfather, CHIN Chear Cheo AKA CHIN Gon Foon (22 August 1871 – 6 March 1939 Seattle), case file no. 39184/2-12 (previously 682, 15844 and 30206)

- Great uncle, CHIN Wing Quong 陳榮光 (5 September 1900 – 1918 Seattle), case file no. 28104

- Great uncle, CHIN Wing Ung 陳榮棟 AKA Donald Wing-Ung CHIN (28 October 1913 – 5 September 2005), case file no. 7031/325 (previously 4985/10-3, 4989/10-3)

I was able to revive family members who had been long forgotten about or completely unknown, by constructing a family tree.

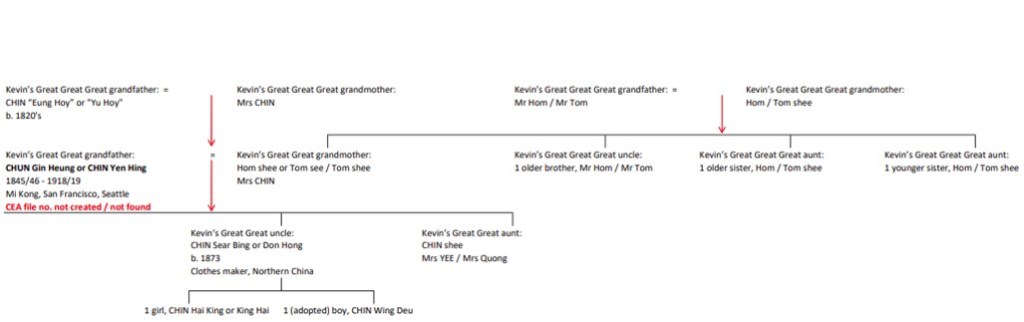

Chin family tree based on three Chinese Exclusion Act case files, National Archives-Seattle

By virtue of these 3 files at Seattle, I was able to establish my grandmother’s:

- Real name / birth name: CHIN Hai Soon (pronounced in the Toisan dialect as ‘Ah Soon’) or CHAN Tai Shin (in the Cantonese dialect). She was a member of the Chin or Chan family; the different spellings are used interchangeably.

- Mother’s name: Love SEETO, also known as SEE TOW Shee.

- Adolescent name: CHAN Mei Chen 陳美珍 meaning treasure, valuable, precious, rare, which she certainly was.

- Place of birth: in the village of Mi Gong, also spelled as Mai Kong, in the town of Hong Gong Lee, in the county of Hoi Ping, in the province of Kwangtung, Imperial China

- Conception date: December 1903. This was based on CHIN Cheo’s file, as he departed Seattle on 31 October 1903, to sail 3 weeks onto Hong Kong, and then a further day to travel to the village near Canton City, Kwangtung Province, to meet-up with his wife, Love SEETO / SEE TOW Shee, whom he had not seen for over 3 years.

- Date of birth: September 1904

- CHIN Hai Soon / CHAN Mei Chen did not see her father when she was born, since he had already left Mainland China, travelled onto British Hong Kong in July 1904 to do business, as he was a merchant / co-owner / manager of Wing Sang Company, 412 Seventh Avenue, South, and Sang Yuen Company, 660 King Street, both in Seattle.

- CHIN Hai Soon / CHAN Mei Chen grew up with her paternal grandfather CHIN Gin Heung (in the Toisan dialect) or CHAN Yen Hing (in the Cantonese dialect), as the only male influence in her life, because her father CHIN Cheo 陳超 lived 59 out of his lifetime of 67 years in the United States. Her grandfather CHIN Gin Heung / CHAN Yen Hing had come back to Mi Gong village from Seattle, 10 years prior to her birth. He had lived in the USA continuously for 12 to 13 years, firstly in San Francisco, then in Seattle, working as a laundryman from 1880 to 1892/1893, and heading back to the village in China prior to his 50th birthday, to celebrate with his family using his hard-earned wealth, and prior to the law requiring him to hold a U.S. Certificate of Residency. No CEA case file of CHIN Gin Heung / CHAN Yen Hing could be found in either San Bruno, California nor Seattle, Washington, as his arrival and departure dates from the USA were too early for Customs and Immigration to have kept records.

- 1st time meeting father: 1912 as an 8-year-old girl, when CHIN Cheo sailed out of Mi Gong, via Hong Kong, to procreate again with Love SEETO / SEE TOW Shee to produce a future brother and future Seattle resident CHIN Wing Ung (case file no. 7031/325).

- 2nd and final time meeting father: 1919 as a 15-year-old adolescent when CHIN Cheo came back with a heavy heart from Seattle to Mi Gong to announce to Love SEETO / SEE TOW Shee of the death of her older brother CHIN Wing Quong (case file no. 28104) in Seattle, and to bring back his remains. CHIN Hai Soon / CHAN Mei Chen remembers the hysteria and grief felt by her mother Love SEETO / SEE TOW Shee over the loss of the number 1 son from accidental poisoning at the drug store co-located within the Wing Sang Company, a business managed and part-owned by her father, CHIN Cheo in Seattle.

- Date of marriage: 1925, as a 21-year-old, to YU Fu Lok AKA YEE Wing Hon, of Num Bin / Nom Bing Chuen, who was a resident of Ohio and Michigan (case file not yet found). CHIN Hai Soon / CHAN Mei Chen, being in China, only met her U.S.-based husband 4 times during their marriage, and 3 of those occasions were to conceive a child, with the last pregnancy being the birth of my mother, YU Siu Lung (later known as Siu Lung YU LEE 李余小濃) in 1936.

- Date of death: CHIN Hai Soon / CHAN Mei Chen died on 29th March 1982 in Num Bin / Nom Bing village, Hoi Ping county, surrounded by close family members, but separated by distance and time from her U.S.-based father CHIN Cheo, two U.S.-based brothers, CHIN Wing Quong and Wing Ung, and her U.S.-based husband, YU Fu Lok / YEE Wing Hon.

Living in China sadly meant my grandmother did not see these 4 U.S.-based family members for many years:

- Father, CHIN Cheo from mid-1904 – January 1913 (the first 8 years of her life); from September 1913 – May 1919 (a gap of 5½ years); from mid-1921 – 6 March 1939 death in Seattle (the last 17½ years of his life)

- Older brother, CHIN Wing Quong, from mid-1910 – late 1918 death in Seattle (the last 8 years of his life)

- Younger brother, CHIN Wing Ung AKA Donald Wing-Ung CHIN, from September 1932 until late 1981 (a separation of 49 years or almost ½ a century, caused by firstly the Japanese invasion of China, then World War II and then the Communist regime in China closing its borders).

- Husband, YU Fu Lok / YEE Wing Hon, from 1938 – 1961 (not seen for 23 years until his death in Detroit).

1982 letter sent from China to Donald Wing Ung CHIN in Seattle to advise of the death of his older sister, CHIN Hai Soon / CHAN Mei Chen (courtesy of the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience, Seattle, item no. 2001_030_001b)

The damage of 60-plus years of the Chinese Exclusion Act was irreparable, as it split Chinese males living in the USA from their families back home in China. It meant daughters and wives did not have strong male influences, and family sizes were kept small. It was only by uncovering the CEA files at the National Archives that I learnt of the many facts that had been kept secret about my family for 140 years.